Oxygen Consulting Client Advisory: Lessons from the first year of climate reporting

By Gerri Ward, Principal Consultant

With the first year of mandatory climate disclosures done, dusted, and uploaded to the Companies Office website, we’ve barely have time to breathe a sigh of relief before embarking on our second year of disclosures reporting.

We thought it might be a useful time, then, to provide some insights[1] into what we’ve learned from year one, what we’d consider some good-practice examples of others’ reports, and some general observations you might find helpful.

Introduction

New Zealand's climate-related disclosure framework, introduced under the Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosures) Amendment Act 2021, came into effect on 1 January 2023 for large financial entities (with more than $1 billion in total assets) and large listed issuers (with a market capitalisation of more than $60 million). The regulation requires these companies to disclose climate-related financial risks and opportunities, in line with the Aotearoa New Zealand Climate Standards (which are based on the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations).

As could be expected, the professional services sector has reviewed, analysed, and published their thoughts on the first year’s climate risk disclosure statements; some more qualitatively (like Deloitte’s report (see below) and some more qualitatively (like this from KPMG).

Source: Creating value through climate transition - Deloitte NZ 2024

The External Reporting Board (XRB) have also commissioned Otago University to do its own evaluation, which is expected by late-2025. The interim report (January 2024) was based on a survey of 45 respondents, and focused more on the need for and benefits of mandatory reporting, than what ‘good’ looks like. We expect the late-2025 review to be far more granular.

The Financial Markets Authority (FMA) – the regulator of the disclosure regime – recently came out with its own review report, covering what they consider went well, where the gaps were, and what their insights were from both, from the first year’s disclosure repots.

Chapman Tripp have helpfully summarised the FMA’s review report here, alongside their own findings and themes out of the first year’s reports.

Investment advisers Forsyth Barr have also released their invaluable insights into what looked good, not-so-good, and risky from an investors’ perspective from the first year’s disclosures for the electricity sector and the aged-care sector; including the potential importance to fundamental value if not managed appropriately. We would highly recommend reading their findings and insights.

Our insights as to the application of the principles of the reporting regime (NZ CS 3)

The XRB have been very clear throughout the development and roll-out of the climate standards that the underlying principles that enable the provision of high-quality climate-related disclosures should be read together with the disclosure standard (NZ CS 1) itself. As noted in the FMA’s recent review, some CREs were found to have presented their climate statements in a way that may have obscured material information for their primary users. The take-out from this is that fair presentation, as always, is key. Providing immaterial or generic information, or repetitively focusing on irrelevant information to users is not going to cut it with the regulator.

Similarly, due to the subjective nature of the reporting, there is a risk that the ‘fair presentation’ of material information does not end up accurately representing a CRE’s financial position and performance. Again, choosing to be clear, complete, and transparent about your climate-related risks and opportunities will always set you in good stead with users and reviewers.

A great example we’ve seen of clear and transparent presentation of material climate-related risks and opportunities is in Infratil’s CRD report, where they clearly lay out their material risks, the anticipated impacts, and Infratil’s strategic response:

Source: Infratil 2024 Climate Related Disclosure

Our insights per pillar under NZ CS 1

Under the New Zealand Climate Standards, all Climate Reporting Entities (CREs) are required to report against four thematic areas: (1) Governance, (2) Strategy, (3) Risk Management, and (4) Metrics and Targets. CREs must also ensure that the parts of their climate statements relating to Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions are independently assured for financial years ending on or after 31 December 2025 (extended for one year after XRB’s consultation and amendment).

1. Governance

The objective of the Governance section is to enable primary users to understand both the role an entity’s governance body plays in overseeing climate-related risks and climate-related opportunities, and the role management plays in assessing and managing those climate-related risks and opportunities. This requires CREs to demonstrate how climate risks and opportunities are integrated into Board and management decision-making processes.

As Boards are ultimately accountable for signing-off these disclosures, this was an area of much interest. Many CREs disclosed that their boards are directly responsible for, and competent in, overseeing climate-related risks and opportunities. The level of integration varied, with some Boards taking a more active role, while others delegated the responsibility to specific sustainability subcommittees or senior management. In some cases, climate issues were framed as part of a broader risk management strategy – either before the disclosure requirements, or as a result of them.

Many of the climate-related risks and opportunities identified by CREs were closely linked to their organisational operations and strategic goals. Where this was the case, Board oversight of these issues was already integrated into existing governance structures and enterprise risk management systems. However, there was evidence that the Standards have led to some improvements, such as the incorporation of climate change risks into risk registers, along with better allocation of responsibility and resources to address the identified material risks.

One of the best examples we saw of what we’d call “good governance” in terms of clear, demonstrated accountability for climate risks and opportunities, and deliberate integration into exiting risk management structures, was from Mercury Energy. Mercury very succinctly and clearly describes the Board’s role in overseeing climate-related risks and opportunities, the responsibilities of the Risk Assurance and Audit Committee, and the frequency and objectives of the meetings of both. They also describe how climate-related risks are integrated within their broader risk management framework and are treated like other risks. They then go on to lay-out the relationship between the responsibilities of the Board, responsible sub-committees and management:

Source: Mercury Energy 2024 Climate Statement

The primary user (or reader) is provided with a clear and detailed overview of how Mercury is considering, managing and responding to climate-related risks and opportunities.

What we like about this approach:

The entity details exactly what the Board and RAAC discussed at every meeting, not just how often the Board and RAAC meets (not pictured).

Key roles, responsibilities, and relationships across the governance body and management are clearly outlined and presented fairly.

2. Strategy

The objective of the strategy disclosure is to enable primary users to understand how climate change is currently impacting an entity and how it may do so in the future. This includes the scenario analysis an entity has undertaken, the climate-related risks and opportunities an entity has identified, the anticipated impacts and financial impacts of these, and how an entity will position itself as the global and domestic economy transitions towards a low-emissions, climate-resilient future.

The FMA has expressed concern recently that some CREs are not adequately explaining how the scenarios help them identify risks and opportunities for their businesses and the process of that analysis. Many CREs do not appear to have integrated scenario analysis into their business processes, and the scenarios are not well-tailored to their businesses.

An excellent example of where a CRE has fully explained their scenario analysis scenario analysis process and how different stakeholders were involved in the process, is Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s climate statement. They provide a clear, simple, and robust explanation of who was involved, how they were involved, how the scenarios were developed, how they were analysed, and what improvements they have identified for next reporting periods.

Source: Fisher & Paykel Healthcare 2024 Annual Report

What we liked about this approach:

We really liked this step-by-step approach explaining the process the entity went through, culminating in the assessment of the resilience of Fisher & Paykel Healthcare’s business model and strategy.

The entity details how different stakeholders were involved in the scenario analysis process, including the specific stages of the process where they engaged.

The entity integrated required NZ CS 3 disclosures around scenario analysis methods and assumptions into the disclosure of the process undertaken, providing the primary user with further contextual information.

3. Risk Management

The risk management disclosure is meant to enable readers to understand how an entity’s climate-related risks are identified, assessed, and managed and how those processes are integrated into existing risk management processes.

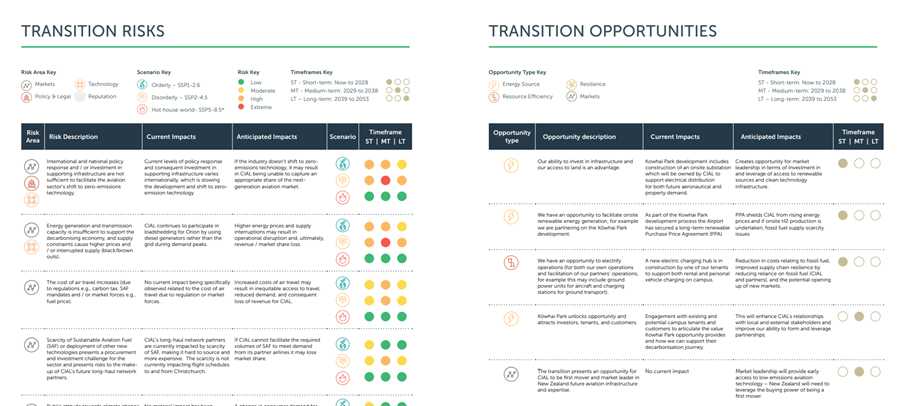

This example from Christchurch Airport very clearly demonstrates this integrated reporting approach, explaining clearly how they measured, assessed and rated their risks within their existing enterprise risk structure.

Source: Christchurch Airport 2023 Annual Review

What we liked about this approach:

Christchurch Airport recognise the challenges and dependencies they are facing, and choose to be straight-up and transparent about them; rather than shying away from them": “We recognise aviation has to decarbonise and although we don’t know ultimately what this will look like in terms of alternative energy sources, what is certain is that it will need a significant amount of renewable energy to enable the transition. We are committed to leaning into this future and being part of the solution rather than the problem.”

They clearly articulate how and when their decarbonisation transition strategy works into and with their “masterplan” overarching strategy.

They describe where and how the accountabilities and responsibilities of their transition actions sit across the business.

Climate-related risks and opportunities are clearly presented as embedded in the broader strategy setting and risk management approach.

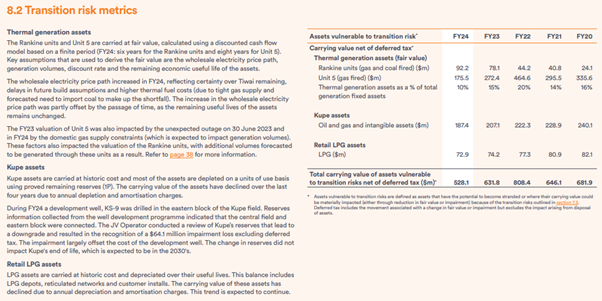

4. Metrics and Targets

The objective of the metrics and targets disclosure is to enable readers (primary users) to understand how an entity measures and manages its climate-related risks and opportunities. Metrics and targets also provide a basis upon which primary users can compare entities within a sector or industry.

Genesis Energy’s report describes the metrics outlined in NZ CS 1, industry-based metrics and other key performance indicators used to measure and manage their climate-related risks and opportunities. They include a robust list of criteria, including:

Genesis’ GHG emissions

Transition risk metrics

Physical risk metrics

Climate-related opportunity metrics

Capital deployment metrics

Internal emissions price, and

Remuneration metrics.

Source: Genesis Energy 2024 Climate Statement

What we liked about this approach:

The internal emission price metric is supported with information about how the entity uses emissions pricing internally, and shows historical changes.

The risk metrics are directly tied to the entity’s specific risks and financial impacts.

All metrics and targets (read in conjunction) are likely to inform the primary user of the entity’s overall vulnerability and exposure to climate risks.

A note on integrated reporting

There is no requirement under the New Zealand disclosure regime for climate statements to be integrated (or not) within an entity’s annual financial report. However, there is a requirement to link to climate statement in an entity’s annual report (where the entity is required to prepare this report).

The most popular approach by far to publishing climate statements in New Zealand has been as a standalone document. Only a fraction (5%) of reporters chose to integrate their CRDs within their annual report (including NZME), and 6% within a broader sustainability report[2].

The TCFD’s recommendations is that the disclosure is fully integrated in financial reporting, and the new Australian Sustainability Reporting Standards requires an entity to provide disclosures as part of its general-purpose financial reports.

In sum: our reckons

Some of the over-arching themes we’ve observed as result of the FMA and professional services firms’ reviews and analysis have shown that you should”

Always err on the side of hyper-transparency, alongside consideration what is material to the users of the report.

Don’t shy away from ambition; but be really clear when and how it comes into play, and where there are critical dependencies, say that.

Identify your risks and opportunities – and then explain how you will/do integrate them into your broader organisational strategy. Saying what they are and then leaving them there unaddressed is not the point of the disclosure legislation.

Disclose the information that is material for your primary users.

Present all information fairly, and provide contextual information to support any claims.

[1] It is important to note that this does not in any way constitute an exhaustive review of all of the first year CRDs, and should not be taken to indicate what constitutes an accepted standard against which disclosures should be measured. Note also that this is a small sample of CRDs available to read on the Companies Office website, and should not be taken as a comprehensive review.

[2] https://www.minterellison.co.nz/insights/climate-statements-the-third-instalment